易

經

Yi Jing

– I Ching, the Book of Changes

– I Ching, the Book of Changes

This famous system of 64 hexagrams plus their commentaries and transformations is at the root of Chinese thought. Tr. Wilhelm (en, fr).

| 52. 艮 Kên / Keeping Still, Mountain | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

current binomial swap trig. opposite flip X leading master X constituent master

The Hexagram

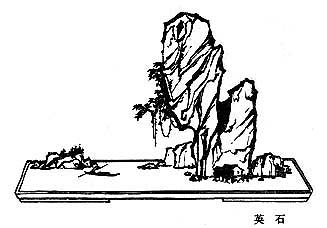

Above KÊN KEEPING STILL, MOUNTAIN

Below KÊN KEEPING STILL, MOUNTAIN

The image of this hexagram is the mountain, the youngest son of heaven and earth. The male principle is at the top, because it strives upward by nature; the female principle is below, since the direction of its movement is downward. Thus there is rest because the movement has come to its normal end.

In its application to man, the hexagram turns upon the problem of achieving a quiet heart. It is very difficult to bring quiet to the heart. While Buddhism strives for rest through an ebbing away of all movement in nirvana, the Book of Changes holds that rest is merely a state of polarity that always posits movement as its complement. Possibly the words of the text embody directions for the practice of yoga.

The Judgment

So that he no longer feels his body.

He goes into his courtyard

And does not see his people.

No blame.

True quiet means keeping still when the time has come to keep still, and going forward when the time has come to go forward. In this way rest and movement are in agreement with the demands of the time, and thus there is light in life.

The hexagram signifies the end and the beginning of all movement. The back is named because in the back are located all the nerve fibers that mediate movement. If the movement of these spinal nerves is brought to a standstill, the ego, with its restlessness, disappears as it were. When a man has thus become calm, he may turn to the outside world. He no longer sees in it the struggle and tumult of individual beings, and therefore he has that true peace of mind which is needed for understanding the great laws of the universe and for acting in harmony with them. Whoever acts from these deep levels makes no mistakes.

The Image

The image of KEEPING STILL.

Thus the superior man

Does not permit his thoughts

To go beyond his situation.

The heart thinks constantly. This cannot be changed, but the movements of the heart–that is, a man's thoughts–should restrict themselves to the immediate situation. All thinking that goes beyond this only makes the heart sore.

Lower line

Keeping his toes still.

No blame.

Continued perseverance furthers.

Keeping the toes still means halting before one has even begun to move. The beginning is the time of few mistakes. At that time one is still in harmony with primal innocence. Not yet influenced by obscuring interests and desires, one sees things intuitively as they really are. A man who halts at the beginning, so long as he has not yet abandoned the truth, finds the right way. But persisting firmness is needed to keep one from drifting irresolutely.

Second line

Keeping his calves still.

He cannot rescue him whom he follows.

His heart is not glad.

The leg cannot move independently; it depends on the movement of the body. If a leg is suddenly stopped while the whole body is in vigorous motion, the continuing body movement will make one fall.

The same is true of a man who serves a master stronger than himself. He is swept along, and even though he may himself halt on the path of wrongdoing, he can no longer check the other in his powerful movement. Where the master presses forward, the servant, no matter how good his intentions, cannot save him.

Third line

Keeping his hips still.

Making his sacrum stiff.

Dangerous. The heart suffocates.

This refers to enforced quiet. The restless heart is to be subdued by forcible means. But fire when it is smothered changes into acrid smoke that suffocates as it spreads.

Therefore, in exercises in meditation and concentration, one ought not to try to force results. Rather, calmness must develop naturally out of a state of inner composure. If one tries to induce calmness by means of artificial rigidity, meditation will lead to very unwholesome results.

Fourth line

Keeping his trunk still.

No blame.

As has been pointed out above in the comment on the Judgment, keeping the back at rest means forgetting the ego. This is the highest stage of rest. Here this stage has not yet been reached: the individual in this instance, though able to keep the ego, with its thoughts and impulses, in a state of rest, is not yet quite liberated from its dominance. Nonetheless, keeping the heart at rest is an important function, leading in the end to the complete elimination of egotistic drives. Even though at this point one does not yet remain free from all the dangers of doubt and unrest, this frame of mind is not a mistake, as it leads ultimately to that other, higher level.

Fifth line

Keeping his jaws still.

The words have order.

Remorse disappears.

A man in a dangerous situation, especially when he is not adequate to it, is inclined to be very free with talk and presumptuous jokes. But injudicious speech easily leads to situations that subsequently give much cause for regret. However, if a man is reserved in speech, his words take ever more definite form, and every occasion for regret vanishes.

Upper line

Noblehearted keeping still.

Good fortune.

This marks the consummation of the effort to attain tranquillity. One is at rest, not merely in a small, circumscribed way in regard to matters of detail, but one has also a general resignation in regard to life as a whole, and this confers peace and good fortune in relation to every individual matter.

je me tais

Le temps qui passe ne tient pas compte d'un retard et d'une immobilité annoncée.

I Ching, the Book of Changes – Yi Jing I. 52. – Chinese on/off – Français/English

Alias Yijing, I Ching, Yi King, I Ging, Zhou yi, The Classic of Changes (Lynn), The Elemental Changes (Nylan), Le Livre des Changements (Javary), Das Buch der Wandlung.

The Book of Odes, The Analects, Great Learning, Doctrine of the Mean, Three-characters book, The Book of Changes, The Way and its Power, 300 Tang Poems, The Art of War, Thirty-Six Strategies

Welcome, help, notes, introduction, table.

Index – Contact – Top